Is there a cure to childhood food allergies?

Is there a cure to childhood food allergies?

By the time I got the car out of the garage, my wife was already on the sidewalk cradling our ten-month-old daughter who was now completely naked and covered in vomit. She launched into the back seat of the car and yelled, “Drive!” My daughter’s eyes were swollen shut and she was painfully disoriented. I raced to Boston Medical Center, speeding through a half-dozen red lights before leaving the car still running in the middle of the parking lot. We sprinted into the emergency room screaming: “Help! Help! Our daughter is in anaphylaxis!”

When we learned a few months earlier that our daughter’s severe head-to-toe eczema could be connected to a dizzying number of food allergies, I honestly wasn’t overly alarmed. I had a couple of friends growing up who were allergic to peanuts, and as far as I could tell, their allergies hadn’t slowed them down. I remember when the nurse was teaching my wife and I how to use the EpiPen, I asked her how we would know if our daughter was going into anaphylaxis. “Trust me, you’ll know,” she responded bluntly. “You see it once and you’ll never forget it.” As our daughter continued to flail, scream and projectile vomit in her mother’s arms in the ER, I now understood exactly what she meant. I was never going to forget this experience—no matter how hard I tried.

After our daughter was finally stabilized with epinephrine, steroids and antihistamines, we spent a long sleepless night in the pediatric ICU, watching her through the bars of the hospital crib. Twenty-four anxious hours later, we walked back into our apartment where the whole ordeal had started. We learned that a tiny little pea was the culprit for her allergic reaction. Totally shell-shocked, my wife and I agreed that we would do whatever was necessary to never relive that terrifying experience. However, as fate would have it, less than thirty minutes later, our daughter went into what’s known as rebound anaphylaxis, a secondary reaction. And so into the ambulance we went for another sleepless night in the hospital. Clearly, food allergies were infinitely more complex than I had ever imagined.

In the months that followed, my wife launched a crusade for answers. She read late into the night about the modern-day explosion in food allergies, how in the last thirty-five years, the number of children suffering from food allergies had increased by ten times. Today, 32 million Americans have food allergies and the rate of anaphylactic reactions has grown by 400 percent over the last decade. Theories abound for the causes of this explosion in food allergies, from the rise of processed food, to more chemicals in the environment, to an increase in antibiotics, to the multiplying of vaccines. Beyond their physical symptoms, children afflicted with food allergies also bear mental and emotional burdens. They often find themselves sitting alone at allergy-free lunch tables and unable to partake in birthday cakes, pizza parties and the many little events that define a childhood.

In search of ways to treat our daughter’s enflamed eczema and manage her allergies to dairy, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, gluten and soy, my wife willed her way onto long waiting lists to see some of the top allergists in the country. The appointments often left us feeling discouraged. Powerful steroid creams were prescribed to treat our daughter’s eczema, while we would have to keep her away from all her allergens until she was old enough to manage them. Even then, the conventional treatment for food allergies, known as oral immunotherapy (OIT), would only seek to make her allergies “bite safe,” meaning that if she ate, say, a single peanut, she would not go into anaphylaxis. OIT might not enable her to eat peanuts or any of her allergies freely.

As we descended into deeper despair, my wife happened to share our daughter’s food allergy woes with celebrity chef and friend Ming Tsai. “Oh, well we have to introduce you to Amy,” Ming said immediately. When Ming’s son David was diagnosed with extensive anaphylactic-level food allergies as a child, Ming and his wife, Paulie, discovered Amy Thieringer, the founder of A.R.T. Allergy Release Technique, a holistic approach based in Lexington, Massachusetts, that is totally revolutionizing the treatment of childhood food allergies. “The work that Amy does is life-changing,” Ming said. Today, his adult son is completely cured of his food allergies thanks to A.R.T.

“The most amazing part of this work is that a family can come in here so fearful and so scared and I can look at them and say: Your kid is not going to have food allergies,” says Thieringer, who began developing her A.R.T. protocol more than fifteen years ago after her own son nearly died of an anaphylactic reaction. “I’m going to change your life.” Thieringer says, to date, she has cured more than four hundred children of their food allergies through a protocol she has developed to balance and bolster a child’s immune system. “Nobody else is looking at the root of the issue,” she explains. “If you ask leading allergists, they’ll say that food allergies are due to an overactive immune system, but they cannot shift and reset that immune system. That’s what we’re doing.”

“The most amazing part of this work is that a family can come in here so fearful and so scared and I can look at them and say: Your kid is not going to have food allergies,” says Thieringer, who began developing her A.R.T. protocol more than fifteen years ago after her own son nearly died of an anaphylactic reaction. “I’m going to change your life.” Thieringer says, to date, she has cured more than four hundred children of their food allergies through a protocol she has developed to balance and bolster a child’s immune system. “Nobody else is looking at the root of the issue,” she explains. “If you ask leading allergists, they’ll say that food allergies are due to an overactive immune system, but they cannot shift and reset that immune system. That’s what we’re doing.”

Using an FDA-approved radiofrequency machine, Thieringer identifies and treats toxins and other stressors that are overloading an individual’s immune system. In addition, A.R.T. uses a professional-grade probiotic and alkalizing agent, all of which strengthen the microbiome in the gut. Thieringer also integrates cognitive behavioral therapy to mitigate the client’s anxiety response, and gradually introduces allergens, ramping them up slowly until clients can eat them freely. “When these clients first come into my office, their world is very small, they’re very anxious, and there’s no hope,” she says. “We’re giving them hope, where traditional medicine leaves them feeling hopeless.”

While her protocol was initially met with skepticism by traditional doctors and allergists, there is now a clinical trial in the works to document its effectiveness. Perhaps even more compelling is the fact that a number of Thieringer’s patients are children of traditional doctors. Dr. Wayne Altman put two of his sons through her protocol. “We started with traditional methods,” says Altman who is the president of the Family Practice Group in Arlington, Massachusetts, as well as the Jaharis Family Chair of Family Medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine. “First, we saw the traditional local allergist who said get an EpiPen and make sure they don’t eat peanuts or tree nuts, but I became determined to see what else we could do because it made me nervous, both in the present and the future, that there might be some accidental exposure that could be dangerous for them.”

Continuing on the traditional medicine route, Altman sought out a world-renowned allergist and enrolled one of his sons into clinical trials treating allergies through OIT and peanut patch therapy. “Neither of them were really successful,” he says. Then Altman heard about Thieringer and A.R.T. through a colleague that practiced functional medicine. He contacted her and learned about the revolutionary protocol. “Balancing the immune system through radio frequency was new to me; it’s outside the domain of the medical world,” Altman says. “But I’m open-minded, and I recognize that in medicine there’s things that we don’t understand and we can’t see.” Moreover, Altman spoke to a number of Thieringer’s past patients who had been cured by the protocol. “There was enough of a track record to prove that it was working that I thought we should give it a try,” he says. “So I got on the waiting list, eventually got my sons treated, and now they’re cured.”

As a professor at Tufts Medical School, Altman is currently helping roll out a study to be published in mainstream medical research documenting the results of A.R.T. in what he described as “a rigorously scientific manner.” With those studies in place, he believes that A.R.T. will become a mainstream treatment of food allergies. “The biggest challenge is scaling this,” Altman says.

While Thieringer personally has a long waiting list of more than four hundred people, she has spent the last three years training others in her protocol and is in the process of opening A.R.T. centers across the country. “We’re starting a movement to eradicate food allergies,” she says. “We’re scaling this so we can safely see the most amount of people possible.” At press time, Thieringer was in the process of expanding her center in Lexington, Massachusetts, while plans were in the works for New York City and elsewhere across the country.

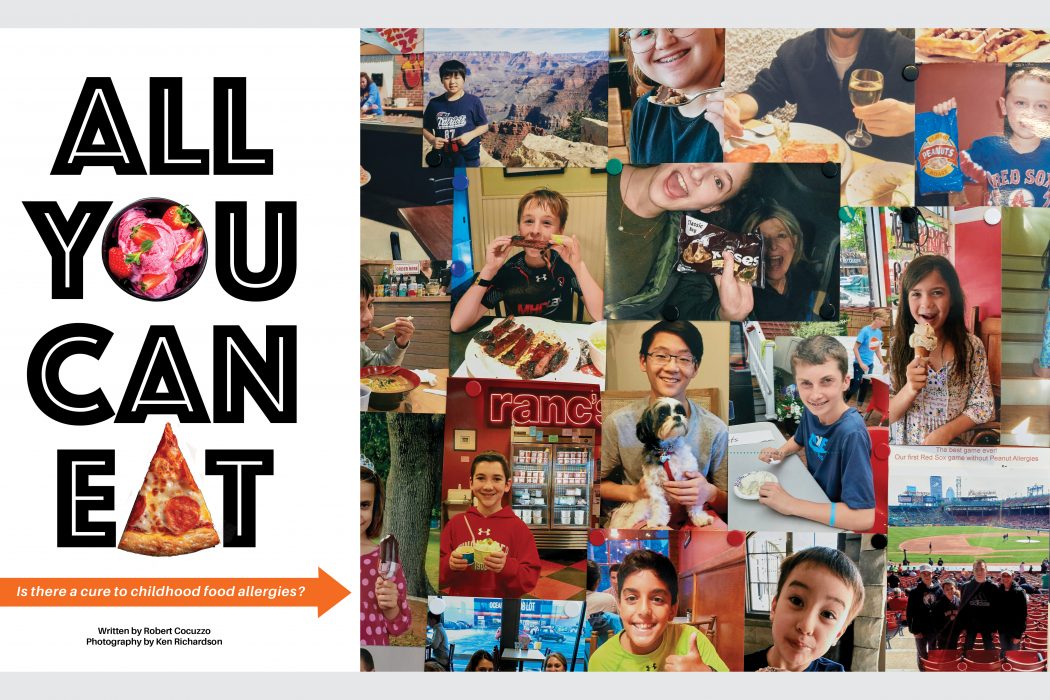

Taking a seat in Thieringer’s office a little more than a year ago, my wife and I were initially struck by all of the photos. Hundreds of smiling children adorn her walls. Some are holding out a slice of pizza, while others are spooning a bowl of ice cream with peanuts on top. Thieringer informed us that our daughter had one of the most severe cases of eczema that she had ever encountered and her half-dozen food allergies were likely to be equally acute. But as she had said to so many families before us, Thieringer promised that she could fix it—and a year later, she is well on her way to fulfilling that pledge.

Taking a seat in Thieringer’s office a little more than a year ago, my wife and I were initially struck by all of the photos. Hundreds of smiling children adorn her walls. Some are holding out a slice of pizza, while others are spooning a bowl of ice cream with peanuts on top. Thieringer informed us that our daughter had one of the most severe cases of eczema that she had ever encountered and her half-dozen food allergies were likely to be equally acute. But as she had said to so many families before us, Thieringer promised that she could fix it—and a year later, she is well on her way to fulfilling that pledge.

Today, my daughter’s skin is not only completely clear of eczema, but she’s already eating eggs, dairy, fish and gluten. And not just in small “bite-safe” doses; she eats a cheese omelet and washes it down with a glass of milk—a breakfast that could have killed her this time last year. Over the course of the next year, we’ll begin introducing treenuts and peanuts. By the time our daughter is able to order for herself at a restaurant, her food allergies will likely be just a distant story that she will have no memory of. Whether our own trauma as parents witnessing her go into anaphylaxis will heal, time will only tell. NEL